How many eggs should a woodchuck chuck?

Nov 12, 2017 · 6 minute read clojureinteractiveSay you’re in a building which has 10 floors. Somebody walks up to you and gives you a box of eggs. He asks if you can find out which is the highest floor in the building from which it is safe to throw an egg, such that the egg remains intact when it hits the ground.

You can make the following assumptions:

-

If an egg breaks then it can’t be reused, but if it doesn’t break, you can go down, pick it up and drop it again from another floor.

-

All the eggs have the same strength. If one of them breaks when dropped from a particular floor, all the other eggs would also break from the same floor.

-

If an egg doesn’t break when dropped from a certain floor, then it will also not break from all floors below that one.

-

If an egg breaks, then it would also break if dropped from a higher floor.

-

It’s possible for the egg to break when thrown from the first floor, and it is also possible that the egg doesn’t break when thrown from the top floor.

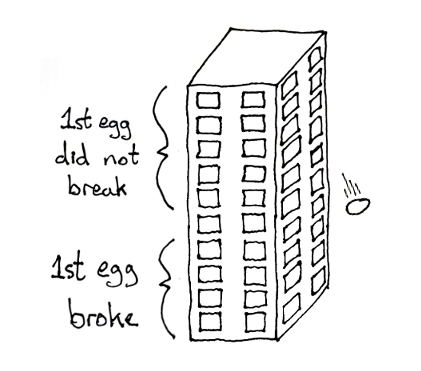

Let’s start assuming you only have 1 egg. The only approach is to drop the egg from the first floor. If it doesn’t break you try again from the second floor etc. Once the egg breaks you will know which is the highest floor that is safe. In the worst case you will need to drop the egg 10 times.

What if we have 2 eggs? Well with 2 eggs you could just use the same strategy with the first egg and save the second one for breakfast the next day. But if you’re not feeling that hungry you could try a different strategy. For example you could directly drop the first egg from the 5th floor. If the egg breaks you know you don’t need to check any of the floors above using the second egg. And if it doesn’t break you don’t need to try any of the floors below. So if you take this approach, in the worst case you only need 6 drops.

But if you think about it a bit longer you will realise that this is not the best strategy. In fact with 2 eggs and 10 floors 4 drops are enough. Think about it and you will see why. (Hint: start at the 4th floor)

We can generalise this problem to any number of eggs and floors. Given no-of-eggs and no-of-floors, what is the min-no-of-drops that need to be performed (in the worst case) to determine the highest floor from which eggs can be safely dropped? Let’s start with the most basic cases:

-

no-of-floors = 0- With 0 floors, it doesn’t matter how many eggs we have. We can’t drop any. -

no-of-floors = 1- With 1 floor, it also doesn’t matter how many eggs we have. We just need 1 drop. -

no-of-eggs = 1- With 1 egg, as we’ve seen above, there is no other strategy except to start at the bottom and work our way up 1 floor at a time. So themin-no-of-dropswould be equal to whatever theno-of-floorsis.

(defn min-no-of-drops [no-of-eggs no-of-floors]

(cond

(= no-of-floors 0) 0

(= no-of-floors 1) 1

(= no-of-eggs 1) no-of-floors))

[(min-no-of-drops 2 0)

(min-no-of-drops 2 1)

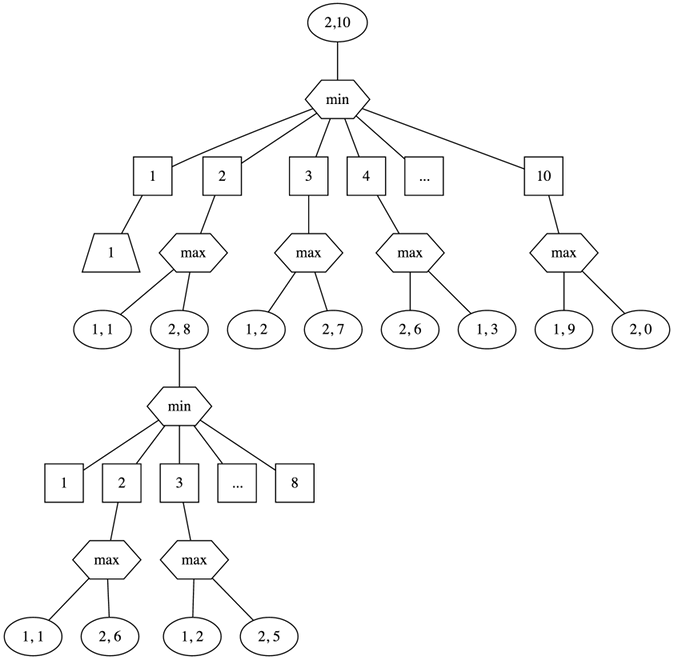

(min-no-of-drops 1 15)]So far so good. What about when no-of-floors > 1 and no-of-eggs > 1? Well we could calculate the number of drops required when starting at each floor. The lowest result is the min-no-of-drops. For each floor f there are two options once we drop an egg:

-

If the egg breaks we call

min-no-of-dropswith one less egg andf - 1floors (because we only need to try the floors below the current one) -

If the egg doesn’t break we call

min-no-of-dropswith the same number of eggs andno-of-floors - ffloors (because we only need to try the floors above the current one)

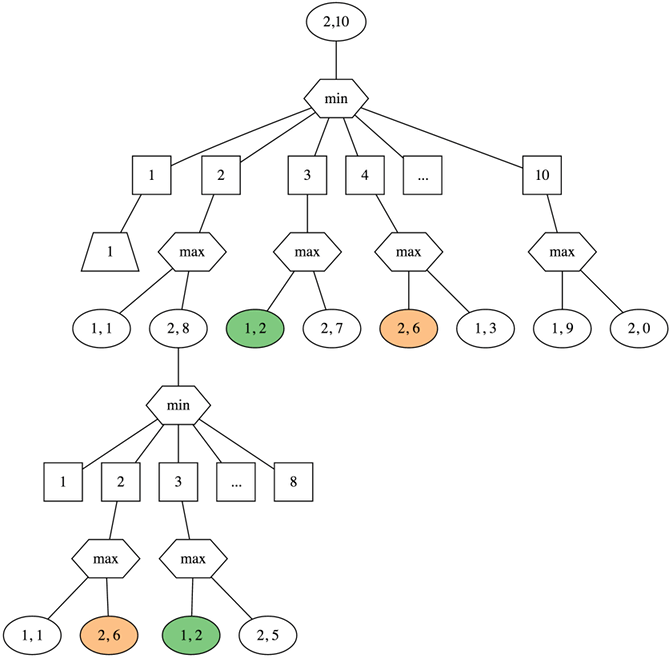

The maximum of these two options is the worst case we’re looking for. If we picture this as a tree we get something like this for 2 eggs and 10 floors:

Let’s add this logic to min-no-of-drops:

(defn min-no-of-drops [no-of-eggs no-of-floors]

(cond

(= no-of-floors 0) 0

(= no-of-floors 1) 1

(= no-of-eggs 1) no-of-floors

:else (let [floors (range 1 (inc no-of-floors))

drops (map (fn [floor]

(max (min-no-of-drops (dec no-of-eggs) (dec floor))

(min-no-of-drops no-of-eggs (- no-of-floors floor))))

floors)]

(inc (apply min drops)))))

(min-no-of-drops 2 5)This works when the no-of-floors is small. But the number of calculations grows very quickly as no-of-floors increases:

[(time (min-no-of-drops 2 10))

(time (min-no-of-drops 2 13))

(time (min-no-of-drops 2 15))

(time (min-no-of-drops 2 18))]However, if you look closer at the graph above, you will see that we sometimes call min-no-of-drops with the same parameters. This is an example of a problem with optimal substructure.

Also notice the function min-no-of-drops is referentially transparent i.e. it will always return the same output if you give it the same inputs. This means that if we store the result when a call is made the first time, we could just reuse the result for all subsequent calls with the same parameters, instead of having to perform the computation again.

We can do this with the memoize function. memoize takes a function as input and returns another function which caches results as they are calculated and on subsequent calls with the same parameters just returns the previous calculation. Let’s look at a simple example:

(defn factorial [n]

(println (str "calculating factorial for " n))

(apply * (range 1 (inc n))))

[(factorial 3)

(factorial 3)]Notice that println is executed twice. Now let’s use memoize:

(def factorial-memoized

(memoize factorial))

[(factorial-memoized 3)

(factorial-memoized 3)

(factorial-memoized 3)]Notice that println is executed only once even though we call factorial 3 times. If you look at the source code it might be easier to understand what’s going on:

(defn memoize

"Returns a memoized version of a referentially transparent function. The

memoized version of the function keeps a cache of the mapping from arguments

to results and, when calls with the same arguments are repeated often, has

higher performance at the expense of higher memory use."

{:added "1.0"

:static true}

[f]

(let [mem (atom {})]

(fn [& args]

(if-let [e (find @mem args)]

(val e)

(let [ret (apply f args)]

(swap! mem assoc args ret)

ret)))))With each call, a lookup is made in a map to see if a previous call with the same arguments was already made. If yes the value in the map is returned. If not the function is called and the result is stored in the map ready for subsequent calls.

Now that we know how to use memoize let’s use it with min-no-of-drops:

(def min-no-of-drops

(memoize

(fn [no-of-eggs no-of-floors]

(cond

(= no-of-floors 0) 0

(= no-of-floors 1) 1

(= no-of-eggs 1) no-of-floors

:else (let [floors (range 1 (inc no-of-floors))

drops (map (fn [floor]

(max (min-no-of-drops (dec no-of-eggs) (dec floor))

(min-no-of-drops no-of-eggs (- no-of-floors floor))))

floors)]

(inc (apply min drops)))))))

[(time (min-no-of-drops 3 18))

(time (min-no-of-drops 4 67))]As you can see the memoized version is much faster.

Note: No eggs were harmed while you were reading this blog post.